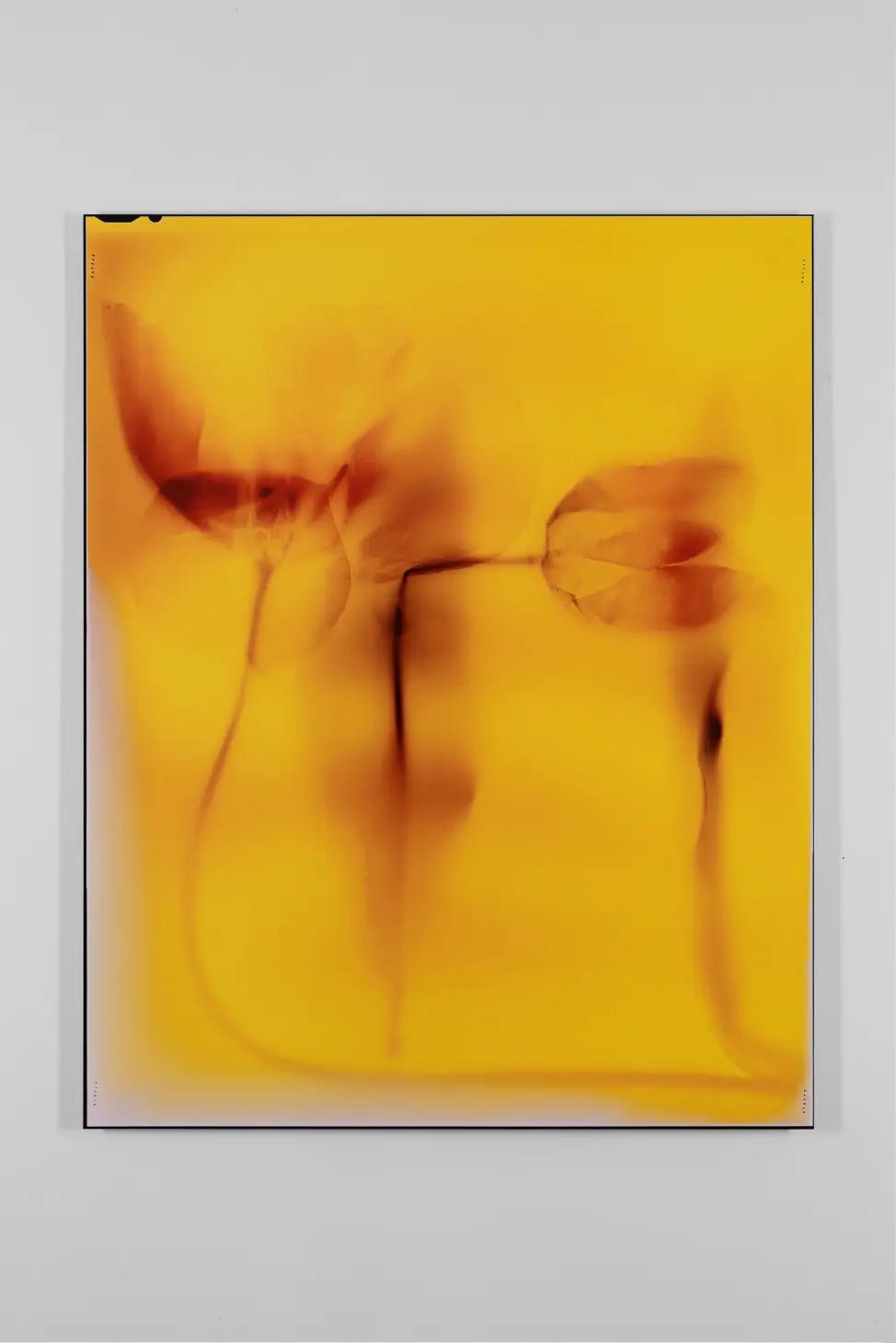

Dye sublimation on aluminum 125 × 100 cm (49 1/4 × 39 3/8 in.) Edition of 2 + 2 APs

About Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili

Born 1979 in Tbilisi, Georgia, Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili is a Georgian-American photographer living in Berlin. Where a photograph is classically understood to freeze a moment in time, Alexi-Meskhishvili’s work undoes such claims of permanence, positing the medium instead as a process of developing and revealing. Typically staging her compositions in the window of her studio or directly on the surface of a negative film emulsion in a “camera-less” method, she melds experimental analogue techniques and digital scanning to make images in which the residual details of this deliberately precarious production shape their subject matter. Homing in on porous boundaries between life and art Alexi-Meskhishvili melds the grotesque, beautiful, abject, feminine and uncanny in ambivalent cohesion.

Making food out of sunlight (sunrise), 2024, is part of Alexi-Meskhishvili's recent series that employs the dye sublimation printing process to create vibrant, ethereal images of tulips—a flower that has become a symbol of remembrance and resistance in Georgia.

About GCRT

GCRT is committed to providing holistic care to survivors of torture, inhuman treatment, and severe trauma. Founded in Georgia in 2000, GCRT has become a sanctuary for those affected by violence, including internally displaced persons, victims of domestic gender-based violence and sexual abuse, youth at risk of developing criminal behavior and in conflict with the law, former prisoners, individuals impacted by the ongoing regional conflicts and Human Rights defenders facing persecution.

GCRT has provided holistic mental health psychosocial and medical services to over 18,000 children and adults. Over the years GCRT has worked in IDP and refugee communities, inside prisons and along the borderlines of Russian occupation.

Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili

Born 1979 in Tbilisi, Georgia. Lives and works in Berlin.

BFA in Photography, Bard College (1998–2003)

Selected Solo Exhibitions

Selected Group Exhibitions

The Tulip as Witness, by Song-I Saba

An ensemble of large-scale, quasi-abstract, almost diaphanous photographic images specifically developed for the outdoor context of the back wall of Kunsthalle Basel. The images are, as with so much of the Georgian-born artist’s practice, a mix of straight photographs, composite images created by superimposing photographic negatives, and explosions of chroma produced in darkroom processes. The works expand the artist’s interest in looking, deftly, at the minutia of everyday life as it is captured and shot through with transparency and light.

London-based arts and culture writer, Song-I Saba, on Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili's portraits of resistance.

‘I didn’t want any flowers, I only wanted

To lie with my hands turned up and be utterly empty.

How free it is, you have no idea how free—

The peacefulness is so big it dazes you,

And it asks nothing…’

Sylvia Plath, Tulips, 1962

Born in Tbilisi, Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili’s work is deeply rooted in the exploration of memory making, visual identity, and resistance in relation to Georgia’s history, as well as its current political climate. But her practice is as poetic as it is political, choosing to highlight emotion and fragility as an asset to the endurance of the human spirit. Having moved to the United States at the age of 14, she graduated from Bard College in New York with a degree in photography, and she has been witnessing the world through various lenses ever since.

Making food out of sunlight (sunrise), 2024 is part of Alexi-Meskhishvili's recent series that employs the dye-sublimation printing process to create vibrant, ethereal images of tulips—a flower that has become a symbol of remembrance and resistance in Georgia. Through Artists Support, Alexi-Meskhishvili has chosen for this work to directly benefit The Georgian Center for Psychosocial and Medical Rehabilitation of Torture Victims.

Thirty-five years ago, on April 9th, the streets of Tbilisi bore witness to a tragedy that would become etched in the collective memory of a people. A peaceful protest held by students advocating for independence was brutally quashed by Soviet military forces, resulting in 21 deaths and hundreds of injuries, most of which were female students. Among those in attendance was Alexi-Meskhishivili’s older sister, who was saved by a surge in the stampede that pushed her into a nearby auditorium when the tanks rolled in.

Commemorating the tragedy of 1989, the tulip has become a fertile symbol of hope and resistance, lining the streets of Tbilisi every April 9th as a poignant tribute to the political possibilities of spring. The tulip series is central to Alexi-Meskhishvili's ongoing exploration of the interplay between public and private realms, using these spaces to trace the threads of resistance woven throughout Georgian history. ‘Through these works, I wanted to honor [the tulip’s] significance by exploring its form in a way that reflects both its delicate nature and its enduring power as a cultural icon.’

The works also pay homage to Florence Henri, a photographer in Berlin whose groundbreaking work in self-portraiture and experimental floral compositions was tragically cut short by the outbreak of World War II. ‘This body of work is a meditation on the persistence of cultural memory in the face of oppression,’ says Alexi-Meskhishvili. In these spectral and fragmented images, the artist’s presence is textured by ethereal remnants of the interplay between light and time. Within the liminal spaces of her images, she crafts compositions that evoke both grand historical narratives and intimate personal connections.

In a recently published essay ‘Letter from the City’ (Flash Art, Spring 2023), Alexi-Meskhishvili quoted from a letter Franz Kafka wrote to his friend Oskar Pollak: ‘We are as forlorn as children lost in the woods...For that reason alone, we human beings ought to stand before one another as reverently, as reflectively, as lovingly, as we would before the entrance to hell.’

It is at the entrance of hell that The Georgian Center for Psychosocial and Medical Rehabilitation of Torture Victims has pitched up its tents and rolled up its sleeves, pioneering a holistic care approach to survivors of torture and severe trauma. The non-profit that Alexi-Meskhishvili elected is dedicated to supporting victims of inhumane treatment. They provide a sanctuary for victims of domestic and gender-based violence and sexual abuse, as well as political prisoners and human rights defenders.

‘Today, with the recent introduction of the so-called “Russian Law,” which threatens to undermine civil society organizations, the work of GCRT is more crucial than ever. This law endangers the very foundations of civil society in Georgia, declaring organizations like ours as foreign agents with the ultimate goal to destroy the entire sector. Our mission is not just about healing individuals; it's about safeguarding the principles of human rights and justice in a region still wrestling with the consequences of its past, and a volatile situation in the present.’ Says Lela Tsiskarishvili, Director of The Georgian Center for Psychosocial and Medical Rehabilitation of Torture Victims.

Artists Support ensures that 100% of the proceeds from this work will be donated directly to The Georgian Center for Psychosocial and Medical Rehabilitation of Torture Victims.

In conversation with Lisa Offermann about Georgian arts and independence

Selected through the Tbilisi Public Art Fund's Open Call, Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili installed a temporary artwork in the upper vestibule of 300 Aragveli, an exemplary architectural site of Georgian modernism. She transformed images of Georgian ornaments that are printed on plastic bags and processed them onto the station's large windows, creating a false stained glass effect.

Lisa Offermann, founder of LC Queisser, Tbilisi, speaks to Artists Support’s Clara Zevi about her multi-generational gallery program and the fight for freedom.

CLARA ZEVI We met many years ago in New York. I think we were actually introduced by Melike Kara, who coincidentally is also participating in Artists Support this month. Tell me about your life in the arts before LC Quessier.

LISA OFFERMANN During my studies I gained experience working in galleries and with artists in Leipzig. I then pursued an internship at Gavin Brown in New York and from 2015 to 2018, I worked in Berlin for Tanya Leighton. During that time I met my husband, Nika, who is Georgian. We maintained a long-distance relationship for two years, and that’s when I started to connect with Georgian artists living in Berlin, such as Ketuta [Alexi-Meskhishvili]. I noticed that while Georgia had a vibrant art scene, there was still ample space for new initiatives.

CZYou grew up in Cologne, was the art scene there accessible to you? Was it exciting?

LO For sure. Cologne was and is one of the most important art cities in Germany. For me, it’s even more important than Berlin. The whole Rhineland is such a rich institutional area. We grew up with the Ludwig Museum and with pop art. The art academy in Dusseldorf was also omnipresent.

CZ What did you know about the Georgian scene before meeting Nika and before moving to Tbilisi?

LO I knew Ketuta and other well-known Georgian artists like Andro Wekua and Thea Djordjadze, from the art scene in Berlin. But everything else I learned by coming to Georgia and meeting more people.

CZ I’m curious about the relationship between the state and the arts in Georgia? Is there funding for the arts?

LO Right now, it’s particularly challenging. Our current cultural minister has replaced all the museum directors with individuals who have a background in prison or security management. People that lack any real understanding of the arts. This has made meaningful collaboration almost impossible. In the past, there was more cooperation—for instance, the government funded the Venice Biennale. However, during COVID, there was absolutely no support for the arts or artists, which clearly illustrates the extent of the government's commitment to the arts.

Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili presented Georgian Ornament at the 2021 photography festival in Arles. The symbols in these works are traditional Georgian motifs that are taken from plastic souvenir bags used in Tbilisi. She reworks and enlarges these images, exploring their relationship to the passing of time and recollection of history.

CZ You started a really beautiful initiative during COVID.

LO We started several initiatives. One of the first was the 13 to Support exhibition. While German artists received substantial financial support from the government to weather the first year of COVID, Georgian artists were left without any assistance. Our response was to organize an online show featuring 13 artists, with all sale proceeds going directly to each artist. It turned out to be a very rewarding project, not only because it provided much-needed support, but also because it introduced us to new Georgian artists with whom we’ve continued to collaborate.

LC Queisser was founded in 2018 and supports experimental, interdisciplinary, and emergent practices while fostering international dialogue between Tbilisi and the larger art world. Alexi-Meskhishvili had her solo show, making food out of sunlight, in which she explored the tulip motif through print, photography and film, at LC Queisser in the spring of 2024.

CZ You’re in the process of cataloging the late Vati Davitashvili’s work, and you work with Elene Chantladze, who is 78. You also have Georgian artists in your program who were born after 1991, when the country declared independence from the USSR. Is it important to you to represent Georgian artists from across generations?

LO It is crucial because there was such a profound lack of representation during Soviet times, which has left many artistic treasures still waiting to be discovered. Although the field of art history is growing both in Georgia and across many former Soviet states, there remains a significant gap in research, especially from the Soviet era and the 1990s. This makes it challenging to fully understand the historical connections and artistic developments of that time. Many artists during the Soviet period were non-conformists, refusing to adhere to the official Soviet canon. What truly interests me now is forging new relationships and creating fresh contexts for these artists, shedding light on their contributions and placing them within a broader historical and cultural narrative.

CZ What is the museum landscape in Tbilisi?

LO There is a National Gallery here, but its structure is quite different from museums in Europe. Many artists’ works are still in their families’ homes because they never trusted—and still don’t trust—the government to properly care for their art. As a result, we have numerous house museums, which are often difficult to access since people are still living in them, and the works are neither archived nor digitized correctly. Only recently have private initiatives begun to conserve and digitize these collections.

For her latest show, Ketuta filmed inside two house museums, and she plans to make ten more films documenting house museums in the city. I believe it’s crucial to record these spaces because they represent a unique form of museum, and we don’t know how long they will continue to exist.

CZ Ketuta has been in your program from the beginning, she was in the gallery’s opening exhibition. How did you come across her work?

LO I first encountered Ketuta’s work through Micky Schubert in Berlin. I admired the gallery and their commitment to several Georgian artists. I vividly remember seeing her booth at Art Basel Statements in 2016 and being struck by the presentation. When I began visiting Georgia, I reached out to Ketuta and arranged studio visits. I was genuinely fascinated by her work, even though I didn't have a concrete plan at the time.

When I eventually decided to move to Georgia and open the gallery, the Georgian community based in Berlin—artists like Ketuta, Thea Djordjadze, and Andro Wekua—introduced me to the scene. Including Ketuta in my first show was incredibly important; it served as a connection point to the city. Although she had collaborated with other artists before, this was the first time she presented her own work. Soon after, I invited her to join the gallery’s program.

CZ The work that Ketuta has donated to fundraise for The Georgian Center for Psychosocial and Medical Rehabilitation of Torture Victims is a dye sublimation on aluminum. Can you explain this technique?

LO Dye sublimation printing involves transferring dye onto materials like fabric, metal, or ceramics using heat. In Ketuta’s work, the dye was transferred onto aluminum. In this process, solid dye particles are converted directly into gas without passing through a liquid state, allowing the dye to penetrate the surface of the material. This results in vibrant, long-lasting colors that are resistant to fading and wear. The vibrancy and sharpness of the result were intriguing to us and created a beautiful contrast with her analog prints.

Galerie Molitor opened in September 2022. The gallery aims to create a discursive environment for contemporary art in close collaboration with intergenerational Berlin-based and international artists. The gallery is committed to developing and piloting models for a sustainable and distributive work environment for its artists and employees.

CZ The tulip is the symbol of resistance and independence in Georgia. It feels so relevant considering the so-called “Russian Law”, which requires NGOs receiving more than 20% of their funding from abroad to register as “bearing the interests of foreign power”. What has the atmosphere been like among your peers in Tbilisi over the last months?

LO Ketuta wanted to comment on the political situation, which is why her show about the tulip emerged earlier this year. At that time, everyone was very tense, stressed out, and attending demonstrations almost daily. Many people were thinking of a Plan B. Often we had to close the gallery because we allow our staff the freedom to participate in the protests whenever they want. During the summer, things relaxed a little. We’re now all waiting for the elections in October.

CZ When you say Plan B, do you mean people were thinking about leaving Georgia, because of the threat to their independence?

LO Yes, many.

CZ Such a large percentage of the population was demonstrating.

LO It was huge. I think the biggest demonstration had around 300,000 people, in a country of only 3.8 million. It became very clear that people understood what was at stake and were strongly against the “Russian Law”. So, we are really hopeful for the elections in October.

CZ We’re keeping our fingers crossed here, too.

Twenty-one questions with design duo, Leorosa

Paolina Leccese and Julian Taffel, founders of the New York/Cologne knitwear label, Leorosa, ask Ketuta Alexi-Meskhishvili about doppelgängers, slogans and simplicity.

LEOROSA What is most difficult to find in contemporary culture?

KETUTA ALEXI-MESKHISHVILI Empathy.

LR What do you find most exciting in contemporary culture?

KAM That it can tell us so much about ourselves.

LR What do you treasure most in your neighbourhood or city?

KAM In Tbilisi I treasure how my daughter can roam, unsupervised on our street all day with the neighbourhood kids. In Berlin, multiple languages spoken in the nearby parks, as well as our proximity to our studios and friends, are all gems.

LR Where do you imagine you would find your doppelgänger?

KAM As a child I imagined her on another planet, which was identical to ours, but with days and nights reversed. I would dream her waking life and she dreamt mine because we were connected in our sleep.

LR Who is an inspirational figure?

KAM Anyone who overcomes their circumstances through their commitment to justice or art.

LR Do you have a soundtrack to your life?

KAM I find soundtracks distracting, even in films.

LR What is good design?

KAM Earth without humans sounds pretty good. Humans did create some good design however: from the Coca Cola logo to Carlo Mollino, from Aldi totes to Chanel 2.55 bags, there is so much to choose from.

LR Where do you find good design?

KAM Everywhere.

LR What should we be reading?

KAM We should be reading Octavia Butler, of course.

LR What is your favorite word in any language?

KAM ორსული. Which in Georgian literally means “two souls” and refers to a pregnant woman.

LR What do you collect?

KAM Trash to make art out of.

LR The best arthouse film?

KAM I always go back to Vagabond by Agnes Varda.

LR What was the first piece of cultural work that really mattered to you?

KAM Having grown up surrounded by art and artists, it is very hard to choose. As a young child I do remember attempting to visualise the vibrancy of colours in Russian fairy tales.

LR What is still a mystery?

KAM Music.

LR What is your favorite representation of simplicity?

KAM Things that appear simple are usually complex underneath.

LR What is your favorite representation of complexity?

KAM Capitalism.

LR What do you find humorous?

KAM Everything.

LR What do you see outside your window?

KAM Trees.

LR Can you define the words “timeless” and “contemporary”?

KAM Something contemporary is inherently related to the particular time of its inception, while something timeless manages to stay relevant in multiple contemporaneities.

LR What is your favorite slogan?

KAM Slow and steady wins the race.