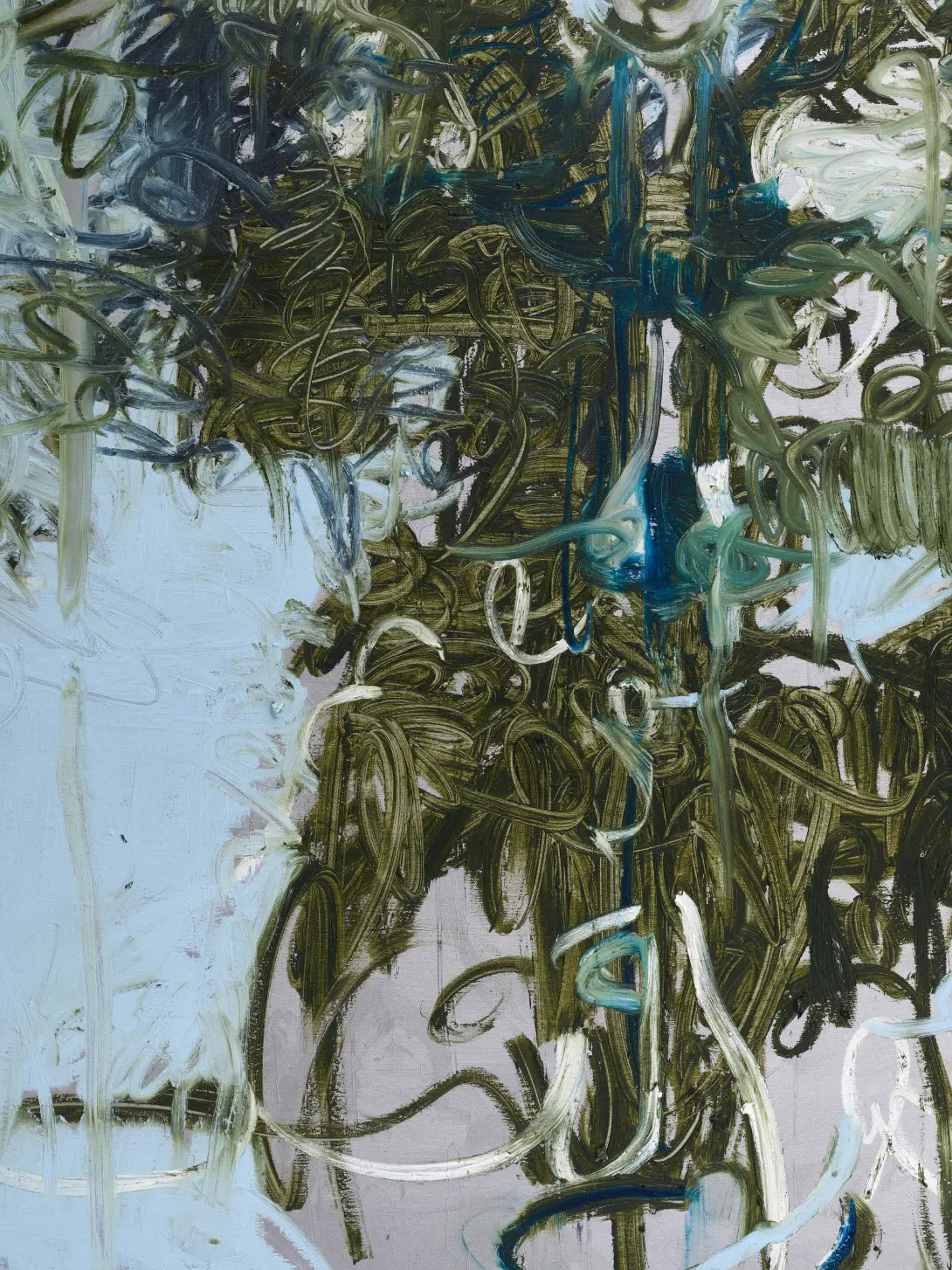

Oil stick and acrylic on canvas 200 x 180 cm (78.7 x 70.9 in.)

€45,000About Melike Kara

Born 1985 in Bensberg, Germany, Melike Kara’s practice encompasses a wide range of media, including painting, sculpture, and photography. Kara is known for addressing issues of displacement, marginalization, and exclusion, focusing on making unheard voices heard and empowered.

Kara draws inspiration from Kurdish tapestries and uses them as a starting point for her gestural abstract paintings that reinterpret her own cultural heritage. Her process of adaptation shifts the narrative away from dominant stories of oppression and instead creates spaces to celebrate the beauty of everyday cultural life and its history, including traditions of the Kurdish diaspora.

About wir für pänz

Founded over 30 years ago, wir für pänz is a provider of care services for children, a recognized independent youth welfare organization and an advisory center commissioned by the City of Cologne.

Wir für pänz cares for children that have, or will face, disability or illness, as well as kids dependent on childcare or who live in disadvantaged areas. Wir für pänz provides a range of services including: advice for parents and care workers, mobile child and youth welfare services, children’s at-home nursing care, mobile integration services, teaching models for schools, early intervention (based on federal initiatives), welcome visits for new parents, mobile assisted living support, family support services, inclusive day nurseries, parent-child groups for disadvantaged communities, childcare finder services and back-up for childcare professionals.

Melike Kara

Born 1985 in Bensberg, Germany. Lives and works in Cologne.

Dusseldorf Art Academy (Rosemarie Trockel), 2007–2014

Academy letter and Protégé, 2014

Selected Solo Exhibitions

Selected Group Exhibitions

Melike Kara in conversation with author Cody Delistraty

The Ludwig Foundation invited Melike Kara to create a site-specific installation, on display at Haus Ludwig from June 29 to October 29, 2024. In her latest work, Kara weaves together tradition and future, exploring the interplay of materiality, transformation, and cultural complexities. The installation explores the interaction between tradition and contemporary – a dynamic that plays a significant role in the daily work of the Peter and Irene Ludwig Foundation.

Melike Kara speaks to Cody Delistraty, journalist and author of The Grief Cure: Looking for the End of Loss.

Cody Delistraty As you know, in much of the West there’s a deep-seated expectation that grieving be quick. A decade ago my mother died of cancer, and from every angle I felt pushed to get back to class, work, “life.”

In the U.S., where I’m from, the average bereavement time off work is only five days. That wasn’t even close to enough time to wrap my head around my mother’s death, of course, let alone to feel like I’d even begun to properly grieve. It seemed to me that there was a real disconnection between the “life of my grief” and “real life” in that socially I was expected to quickly exit the former and re-enter the latter. This expectation, I think, made my grieving even more complicated and challenging.

Melike, you’ve lost close family and friends in recent years, too. Can you describe those losses and the process of returning to the studio to paint?

Melike KaraThat is a complex question to answer. I view the painterly process as one possessing its own rhythm. My readiness to open up to painting and devote myself to its very own pace merges with the moment when the painting itself decides to flow.

Being able to return to my studio and give myself over to the natural flow of painting and the movement of my hand has been a great gift within my grieving process. It feels like a silent embrace, retrieving me, rescuing me into the grace of nothingness. Grief and loss have a way of rendering us more sensitive, calm, and in closer proximity to the core of “being” and everything “that is in existence”. I feel an immense gratitude when pondering the solace that going to my studio affords me. Since I have reserved a little space there to make an altar for my deceased relatives and ancestors, I have the possibility to connect with them and invite them to be present with me while I work.

CD So well said. Gratitude in grief is crucial. So too is the expansiveness with which you’re clearly thinking about grief. The term “ambiguous loss” is one that I keep returning to when thinking about how we legitimize—or delegitimize—certain kinds of grief. It was coined in the 1970s by Pauline Boss, a now-90-year-old emeritus professor at the University of Minnesota, to mean any loss in which one does not “have all of the facts.” So that could be, she said, a psychologically absent father (the loss of an emotional connection) or a family member who went MIA as a soldier in Vietnam (uncertain of whether he’s alive). The popular notion of “closure” proceeds from this.

Most people have a desire toward certainty, particularly in loss, but it sounds like you’re content to live within it, which, having experienced my own loss, is the wisest choice, I think. Too often people search for end points like closure, an idea reified in part by a misinterpretation of Elisabeth Kübler-Ross’ “five stages of grief,” which ends in “acceptance.” In fact, I don’t think closure really exists at all.

In your own life, how do you think about the phenomenon of “closure” and similar expectations around grief?

MK I agree with Pauline Boss in there being no strict rules—no recipe for how to grieve or gently survive the loss of a person. Speaking from my own experience and that of my family, I can say that losing a loved one is not meant to be something that ever heals fully. The idea of this does not even exist within my life. Rather, it feels like our continuous effort to talk about the deceased may allow us to keep their presence with us. Within this process, grief simply takes on a different shape and finds a new place in our lives. We allow our grief to come and go, to present itself in various ways, and to take the shape it needs. To me, it feels as if the people we have lost transcend our memories and land in our hearts.

Kara developed a site-specific, extensive work for the Schirn rotunda. In large-format works she combined photographic material with paintings that refer to patterns from traditional knotted or woven tapestries. Her artistic process here used bleach, and the associated process of abstraction created an examination of change and blank spaces within a specific cultural narrative. Sculptural elements recalling pavilions and pools refer to the architecture of Schirn's rotunda, which is accessible to the general public.

CD That’s beautifully put. In a previous conversation we had, we talked about how one part of your artistic practice is placing photographs of your grandmother—who you lost and to whom you were deeply connected—throughout your work. It made me think about when my mother was in an at-home hospice during the days leading up to her death, and I interviewed her. This idea was to have a record of her, not unlike a photograph.

My dad, brother, and I all sat at our kitchen table and asked her questions. Some were trivial, like her favorite ice cream flavor; others were more profound, like what she wanted to tell my brother and me on our wedding days. Yet for years after she died, I couldn’t bring myself to listen to those recordings. They felt too raw, too real—proof that she was truly gone. When I finally did sit down to listen to them, on a lonely evening when I was living in Paris, I found it to be a breakthrough in my grief: hearing her voice, sitting with it, and realizing that these were audio files I would return to my entire life. I felt uniquely unburdened.

How does having those photos of your grandma—and placing them in your work—affect the way in which you’ve coped with her passing?

MKMy grandmother Emine was my connection and conduit to my own Kurdish roots. Being in her presence truly made me feel and learn what it means to inhabit and live a Kurdish identity. She encompassed our rituals, histories and stories, food traditions, and prayers. Her passing ignited a burning curiosity and desire within me to delve into my Kurdish roots.

It has become essential that Emine remains an integral part of my inquiry into my heritage—how I represent it and work with it.

When my grandmother started suffering from dementia, I encountered the beginning of a process marked by perpetual farewells. It made me confront the emotion of having to let go of my access to this person, one I hold so dear. As I accompanied her passing, a feeling of deep gratitude and solace came over me.

CD That kind of quietude in loss seems so rare. In some ways, it’s of a different time. It makes me think of the historian Philippe Ariès, who called the 18th century an era of “tamed death” because of the ways that loss and grief were socially expected and woven seamlessly into daily life.

That changed by the 20th century in the West, of course, when grief began to be driven into the private sphere. Freud proposed a form of grief as something that might be solved in the therapist’s office; the political necessity of keeping grief quiet became paramount with the unpopularity of the U.S. entering the First World War (seeing so many caskets coming home); the rise of happiness culture and “self-care” that discouraged talk of death and loss; and the disintegration and atomization of communities that has come to define so much of the 21st century. All of this led to a silencing and privatizing of grief, which I find—and many anthropologists and sociologists have found—to be enormously detrimental to how we grieve as a society.

It makes me think of the vitally public nature of your installations, many of which are sites to remember your family's history and those of the displaced Kurdish people. How does it feel to share this history—much of it largely of erasure and loss—with a wider public, bringing this loss out of the shadows in a way?

MK Despite obliteration, loss, and displacement being integral parts of the Kurdish people’s history, I have chosen to never treat them as the sole focus of my work. Instead, I seek to shed light on the beauty of the Kurdish community, the memories of it, our shared rituals and – despite our diversity – everything that unites us.

Within my installations, I endeavor to create spaces that allow for and demand a different reading and performance of history. They are spaces for everyone. They speak to a collective Kurdish history and my own family’s history. They are in symbiosis with the architecture of the space I’m working with and they also stand independently. Depending on the space—whether the installation is in a room or a courtyard—spectators will encounter the work differently. Sometimes they are in the middle of it all; other times they look inside through a window. I create spaces where the viewer may spend some time and feel the presence of the history of a people without fixed roots, a people that managed to spread their roots to new places.

CD Your donated painting is part of a series where you’re at once referring to your cultural heritage, specifically traditional Kurdish patterns and motifs, and reworking them. How does the act of painting these new forms, which are entirely your own, connect you to your ancestors?

MK As a foundation for each painting, I use a pattern derived from Kurdish tapestries of different regions. I allow for space where both the painting and the pattern can grow organically and freely. Starting as a backdrop, the patterns gain agency to weave their own history on the canvas. The titles of my works reference the patterns’ places of origin.

Through the Kurdish people’s forced migration, weavers seized the freedom to adapt motifs from their new surroundings. What I have in common with these women that came before me is the wish to freely select traditional patterns and alter them to my liking. I let them dissolve and cross over into a completely new realm of painting, one that is stretching its roots into the here and now.

Cody Delistraty is a journalist and speechwriter. He has worked as the culture editor of the Wall Street Journal Magazine, and his writing has appeared in the New York Times, the Atlantic, the Paris Review, and New York. His new book The Grief Cure: Looking for the End of Loss is out now.

Wir für pänz's Development Director on caring for Cologne's most vulnerable children

Artists Support speaks to Andrea Brewitt and learns about the people and programs that have been keeping the kids charity running for over 35 years.

ARTISTS SUPPORT Wir für pänz was established to provide specialized care for Cologne kids. Tell us about the organization now, 35 years on from its inception.

Andrea Brewitt We started as a small children's nursing service. At the time, children with serious illnesses could not be cared for at home, they had to be treated in hospital and couldn’t live with their families. We now have a team of 242 employees, not just committed to ensuring that sick kids can be treated and cared for at home, but also helping to provide many different services for vulnerable children and their families. We have youth welfare and family support services, integration assistance, a daycare center, a family house, a counseling center and many more programs for children.

AS Tell us about the people that work at the organization.

AB It’s a multi-professional team consisting of pediatric nurses, intensive care nurses, social workers, pedagogues, educators, physiotherapists, therapists, pedagogical school counselors, social lawyers and social-workers. In addition to our internal staff, we also rely on a complex network of supplementary support services and we work closely with Cologne's children's hospitals, pediatricians in private practices, the health authorities, youth welfare offices and social welfare offices of the City of Cologne.

ASWhat is wir für pänz’s current greatest need?

AB In Cologne, a city that is very expensive to live in, there is a shortage of well-qualified people in every sector. We currently have more than 80 vacancies for social workers, nurses, pedagogical school companions and specially trained childcare workers.

In 2015 Arcadia Missa established as a commercial gallery after running as a project space since 2011. Arcadia Missa Publishers produces an annual publishing programme, composed of the journal How to Sleep Faster, artist and writer novellas, and occasional anthologies.

For her first institutional solo exhibition in Switzerland, Melike Kara continued her exploration of Kurdish traditions and questions of historicization, tradition and community. She realized site-specific works in a large-scale installation that transformed the space of the Kunst Halle Sankt Gallen into her own visual archive.

AS For over 15 years your team has been running groups for young families that need support. Who can attend these and what resources do you provide?

AB Anyone can attend. Most of the families we serve in our Parent-Child groups live on the poverty line and lack basic necessities. Many have a migration background and are in Germany without any family support. We provide the parents, often very young parents, with basic knowledge on topics such as health, nutrition, care and education of their baby or toddler.

AS Melike Kara is donating a new, large painting, made specifically to raise funds for wir für pänz. The work is worth €45,000, how far does a donation of this size go in your organization?

AB It goes a long way. Especially considering that for many of our programs there is no federal funding. Some of our services, such as youth welfare, integration assistance and outpatient pediatric nursing are financed by the City of Cologne and by health insurance companies. Our other programs, including the Parent-Child groups, are financed entirely by donations. To give you an example of what the generous donation could achieve, the Parent-Child groups cost €9-18,000 per group, per year, depending on the location and number of participants. So, this donation could cover Parent-Child groups in three different neighborhoods for an entire year. We offer the groups in four low income areas in Cologne: Ehrenfeld, Ostheim, Mengenich and Nippes. They are free and have a low threshold so as you can imagine, we have a long waiting list.

Olive trees and Munzur, a poem by Melike Kara

a mixture of both

would be the perfect place

where I could trace

everything about you,

the outline is black you say

to me a light pink

do colours even matter

they tell me one step after the other

and that’s supposed to heal everything

I was five

when I saw this pain for the first time

while I sat on the stairs

and the magician waved