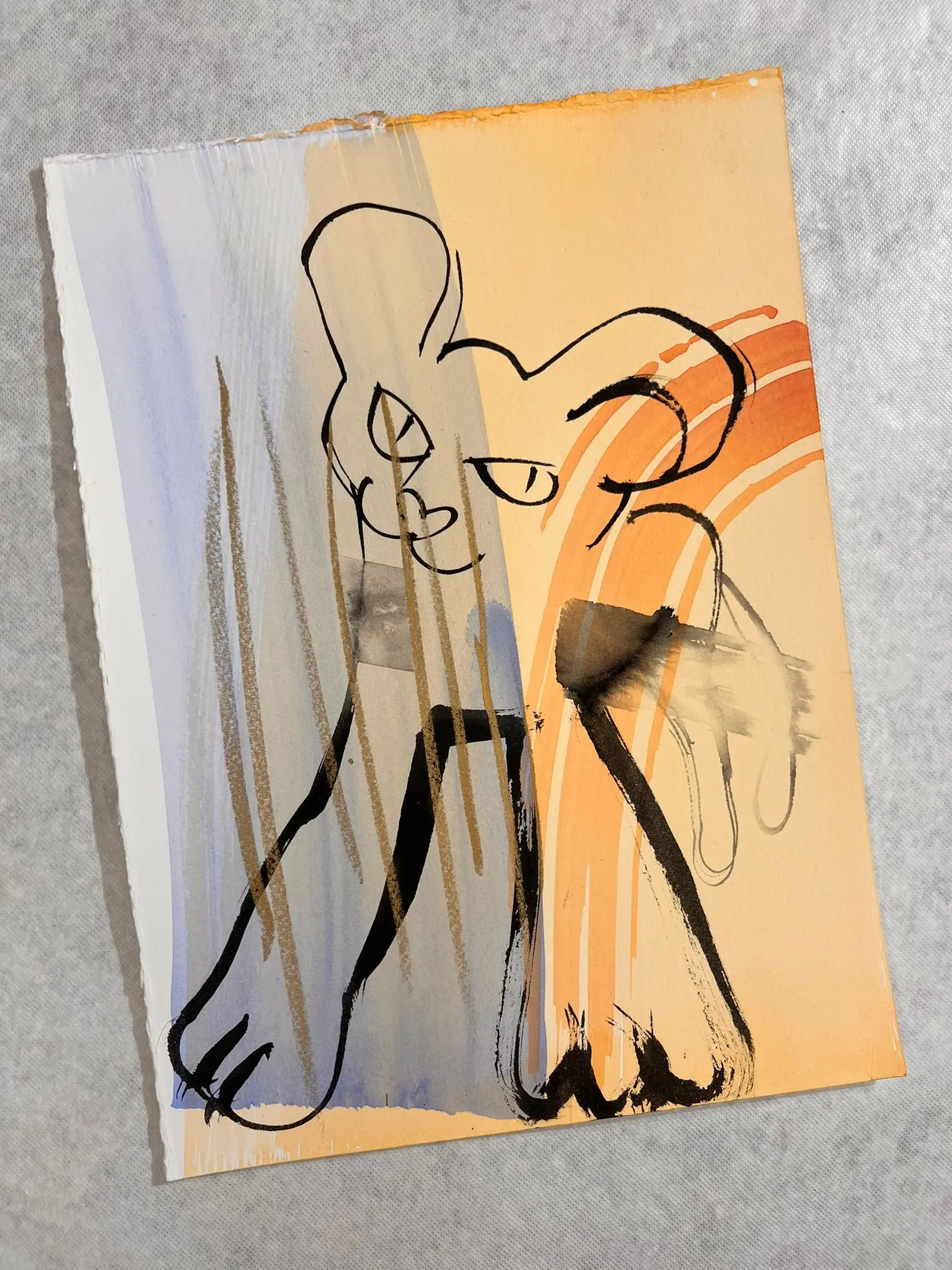

Watercolor and acrylic on paper 38.1 x 27.9 cm (15 x 11 in.)

$20,000About Camille Henrot

The practice of French artist Camille Henrot moves seamlessly between film, painting, drawing, bronze, sculpture, and installation. Henrot draws upon references from literature, psychoanalysis, social media, cultural anthropology, self-help, and the banality of everyday life in order to question what it means to be both a private individual and a global subject.

A 2013 fellowship at the Smithsonian Institute resulted in her film ‘Grosse Fatigue,’ for which she was awarded the Silver Lion at the 55th Venice Biennale. She elaborated ideas from ‘Grosse Fatigue’ to conceive her acclaimed 2014 installation ‘The Pale Fox’ at Chisenhale Gallery in London. The exhibit, which displayed the breadth of her diverse output, went on to travel to institutions including Kunsthal Charlottenburg, Copenhagen; Bétonsalon – Centre for art and research, Paris; Westfälischer Kunstverein, Münster, Germany; and Tokyo Opera City Art Gallery, Japan. In 2017, Henrot was given carte blanche at Palais de Tokyo in Paris, where she presented the major exhibition ‘Days Are Dogs,’ She is the recipient of the 2014 Nam June Paik Award and the 2015 Edvard Munch Award, and has participated in the Lyon, Berlin, Sydney and Liverpool Biennials, among others.

Henrot has donated a second work in support of her chosen cause.

About Amazon Frontlines

Amazon Frontlines (AF) builds power with Indigenous peoples to defend their way of life, the Amazon rainforest, and our climate future. AF partners with Indigenous nations of the Upper Amazon between Ecuador, Colombia and Peru, who collectively govern over 2 million hectares of rainforest territories with immense benefits for climate and biodiversity.

AF bolsters Indigenous-led organizations to achieve significant climate impact. With their partners, AF is forging a new model of forest conservation that puts necessary skills, tools, resources and networks in the hands of Indigenous leaders on the frontline of the climate crisis.

Camille Henrot in conversation with ISOLARII's Sebastian Clark

Grosse Fatigue (2013) for which the artist was awarded the Silver Lion at the 55th Venice Biennale was created through a Smithsonian Artist Research Fellowship. Henrot was granted permission to film the collections of the Smithsonian Archives of American Art, National Air and Space Museum, and National Museum of Natural History in Washington, D.C. Over the course of 13 minutes, the video tells the story of the creation of the universe through a cascade of images that pop up, collide, and implode across a computer screen.

Founder of publishing house ISOLARII learns about Henrot's series 'Biting the Hand that Feeds', and finds out why Amazon Frontlines has the artist's trust.

SEBASTIAN CLARK When I saw this series of work, I felt something entirely unexpected - I was a child again, playing Crash Bandicoot—

CAMILLE HENROT Crash what?

SC Bandicoot.

CH What’s a bandicoot?

SC A kind of marsupial, I think. But in this case, a virtual one. It was a video game in which, as in most video games, you move through space, literally crashing through things and with that learning a new language, spatial and also verbal. But because it’s a video game, you do all this with your fingers so there’s a conjoining of dexterity and language acquisition. It was a feeling I had completely forgotten and I was put in some kind of neuroplastic state again, caught between feeling something and having articulated feelings. Tell me about the origin of this series.

CH Biting the Hand that Feeds was started in 2020. It began with a lot of rage and anger – pure anti–capitalist rage but also anger at our struggle for communication around the COVID crisis. What to do? What to say? During this time, we – as artists – were all clamouring for attention: “Look, what I’ve done!” Like children saying: “Mom, look, I just did this.” Whatever stupid watercolour was done, we would push it online in a fight for attention. In this deranged attention–vortex, there was a feeling of anger both towards class disparity and social insensitivity that included artists because we were not able to articulate politically as adults. Instead, we were just scrambling for narcissistic attention – imagine toddlers asking adults for candy. This is why I chose the figure of a child dressed as a cute dog or cat outfit and she’s doing puppy eyes.

SC It’s a very political body of work, but does not immediately strike as such.

CH No, I don’t like my work to be overtly political. I like any political connections to be subtle. Drawing is something quite subconscious – while I’m drawing, I don’t really know what’s going to happen. Like most people who draw a lot, I draw to find out. Sometimes I start a character and I don’t know: Who is this person? What does she want? Who is she? I begin with an idea but sometimes a character who was meant to be charming and cute becomes aggressive, a kind of predator – or vice versa. Sometimes a predator turns into a victim. In this painting, the little girl in a cat costume is ambiguous, you don’t know what she wants, whether she’s a positive or negative character.

In Jus d'Orange, words and images run after the themes of melancholy, failure, injustice, and hope in a unique exhibition display conceived specifically for the first floor of Fondazione ICA Milano in the shape of a kaleidoscopic installation. Back and forth, to-and-fro, text and image inspire one another—ongoing and unending—intoxicated by life’s many interferences.

SC I think that’s where the politics in your work comes through, in its ambivalence. It is there, in the phrase itself, “Don’t bite the hand that feeds”—

CH It’s the opposite, “Bite the hand that feeds.”

SC I guess that proves the point. The actual idiom is so deeply ingrained, through repetition, that it’s difficult not to say the opposite. And that’s how power is maintained, through our habits and speech patterns. It is of course at moments like this, when politics seem to disappear entirely, that mechanisms of power are most forcefully at work. Your work, in its ambivalence, plays with this dissolution of power.

CH Yes and I feel tenderness as well as irony for characters in positions of power, as much tenderness and irony as I feel for characters in positions of dispossession. I identify with the underdog, but I’m also aware of how capricious underdogs can be in their rage, envy and desire but also in their ungratefulness and absence of strategy. This relates to the child in these drawings; a concept of tenderness and criticality is cast across the series. In this new configuration, I feel like society is treating “us” as children – consider Google’s colorful logo, how they spy on our desires then recycle them back to us.

SC The mantra of UI [user interface design] is “don’t make the user think.” The literal interfaces between systems of control and ourselves are patronising by design–via our thumbs and fingers, no less.

CH There is something about the question of need, fulfilling and abusing a situation of need. That’s why “bite the hand that feeds” – because you have a system that, while speculating on your needs, is not tending to them. We are being fed but in a way that’s predatory.

SC “Bite the hand that feeds.” The title simultaneously invokes your hand.

Chisenhale Gallery presented the first UK solo exhibition by French, New York-based artist, Camille Henrot. Entitled The Pale Fox, this installation developed from Grosse Fatigue, 2013 – the film Henrot presented at the 55th Venice Biennale, 2013, for which she was awarded the Silver Lion for most promising young artist. Demonstrating the breadth of Henrot’s output, this exhibition comprised an architectural display system, found objects, drawing, bronze and ceramic sculpture and digital images.

CH The hand is an important motif in my work. Here the hand is also me because I feed my family, I’m spoon–feeding my children and I’m providing for them economically. So there’s a certain sense of self–aggression too. But my hand draws too and I was highly attuned to this because these were the first drawings I made after I broke my hand in an accident. With some distance, I now recognize how their lines were influenced by my handicap. There is a roughness lacking in other drawings.

SC Did you feel like you were relearning something? In English, we have this phrase: “muscle memory.”

CHYes and I discovered that it’s not the hand that draws but rather the shoulder. When I started drawing again, I realized I could draw without my wrist but with my shoulder. I use calligraphy brushes that are smooth and flexible, they work best when you apply zero pressure and work really fast. It's almost more like dancing, it’s a gesture that has to be very light and very fast and to be good, it has to be careless.

SC The philosopher Michel Serres had a somewhat cryptic, absurd line that I love: “there is no history of the crab.” An expert of crustaceans would no doubt be angered by this, but Serres’ point was that with a claw—it’s all one movement, pure repetition, monotony–and the hand can do anything: draw a bow, play a video game, paint. Hands are de–specialised and it is their endless capabilities that not only create possibilities in the world, but also create the potential to make history. That’s the warning, or rather the challenge, of “don’t bite the hand that feeds you:” ‘do you dare break rank with the regimen, and repeated motions, of power?’

CH Sebastian, the series is titled “do bite the hand that feeds you.” It’s funny you keep thinking the title is “don't bite the hand that feeds” because when I started my series “Dos and Don'ts,” one of the books I used was simply called “Don’t.” It always started with don’t – “don't hold your umbrella inside, don’t move with your chair at the table.” When I was looking at this with a friend, she said: “It’s funny that when you say don't, you immediately think do.” We can represent actions but we cannot represent their absence. If I tell you “don’t slap your napkin,” you already hear a napkin slapping and you see the napkin, right? I found that interesting. I was even considering calling my Hauser and Wirth show “Don't” because it’s such a strong word that we just don’t have in French. I remember when I learned you say “it’s lovely weather, isn’t it?” That is quite weird, isn’t it? The negation in English was exotic to me.

SC You’re right: “isn’t it?” literally, asks you to question the authority of the person, but because it is such a standard phrase, we don’t take up the offer. In fact, it has the inverse effect: “isn’t it?” makes you acquiesce and respond “you’re right.” I think French speakers seem to be more aware of how power is at work in language.

CH But English has so many ways to talk about power, so many expressions for power. Because my works often deal with power dynamics, when it comes to titling them – I like to look at all your verbs: “domesticate,” “constrain,”“shape”… there are multiple words for “control” in English.

SC [laughs] I guess the English are used to being subject to those in power. Or find a way to accommodate them in language. I guess it’s a “chicken or the egg”.

CHI think language is more a vehicle of power than its origin, thinking about the chicken and the egg. We live in a society saturated by language and this is a thought I have some disagreements with. Why is society so language–centric? How has language become an ally of authority, power and oppression? Literature and poetry were once a freeing force because they would create confusion and with that open words to different meanings. Literature and poetry thus became spaces of complexity and nuance, both of which we desperately need. Whatever instigates disturbance, nuance and inversion of meaning – like a glitch in the system of language – also creates a necessary space through which to think.

SC That is the inherent optimism of your work: it is invested in finding a tear in reality through language, and this is what poetry is.

CH I wonder if we can say that all pessimists are merely optimists challenging the status quo. When I think of optimism and pessimism, my mind begins to flip them like a coin.

SC There is an expression: “Pessimism of the intellect, optimism of the will.” I’d be interested to learn of any historical examples of pessimists being tricked into being optimists.

CH In French literature, there are many pessimistic figures who are acerbic and ironic but ultimately from an optimistic perspective: they want only to change the world. Voltaire certainly, but also Montaigne.

Camille Henrot presented a set of newly commissioned sculptures and paintings from her Wet Job (2020-21) series at The Lewis’s Building. In these works, Henrot makes use of the familiar art-historical trope of the mother and child in order to foreground obscured aspects of motherhood and their reflections in society at large. The overriding theme of alienation is crystallized in the figure of the woman expressing milk with a breast pump.

SC It is this capacity to maintain optimism while looking soberly at reality – another ambivalence – that is so important to addressing a crisis like that of the Amazon. Could we talk about Amazon Frontlines, why it’s important to you and why they need support?

CH The Amazon is perhaps the most important place to preserve because biodiversity is highest there. It also plays an important role in slowing down climate change. Most people who live there do not have the resources to fight back against predators, whether they be governments or multinational companies or drug cartel militias. Forces are acting to destroy the forest but in front of these powerful groups are people who have lived there for centuries. Thankfully, these persistent people are getting more organised and more support. I have followed Amazon Frontlines for a while and really believe in everything they do. Of course, the Amazon isn’t just Brazil, it’s Ecuador and other countries too – the charity is importantly transnational. It’s also grassroots and in my experience, Indigenous organisations make the most impact.

SC It’s not simply “Let’s stop the deforestation of the Amazon” — a worthy cause in and of itself – it’s also building networks to preserve and defend culture, language, as well as biodiversity. It’s an incredible organisation.

CH There can be conflict between ecological organisations and local people. I trust Amazon Frontlines because they don’t separate nature from the experience of those who live with it. The network they create recalls my arborescent way of thinking. It’s not a linear system, it’s a spiderweb.

SC I think arborescence is the right word for everything we’ve been talking about.

Part of an exhibition of site-specific works for Frieze Sculpture at Rockefeller Center, Inside Job installed in Rockefeller Center’s Channel Gardens. Evoking both the shape of a shark and also the beak of a bird, the work explores concurrent themes of threat and tenderness.

CH It’s a gift and a curse. Every time I start a project, I draw all the possibilities and they grow like a tree. I’m also fascinated by arborescent narratives wherein you choose your own adventure. It’s natural for me to think through the potentialities and I need to map them all before making any decisions because I get FOMO. Am I going to miss an important direction? Will one be more interesting than another? I need to go down these rabbit holes very quickly and come back, only then am I able to make a decision. I like exploring and wandering through possibilities, I need it in a way that is borderline neurotic. I have come to accept this and so have the people I work with. Although we try to limit these movements a bit, I recognize they are why I’m so fascinated by systems, but also so critical of them: each one carries this certain madness.

SC Your work is like being inside a little language model; one that’s hieroglyphic, polyvalent, ambivalent. For me, that is the experience of this arborescence.

CH Arborescence basically means having choice. The thought that words have two or three meanings is a way of opening up the world and making sure there’s no room for fascism in language. For me, arborescence is an image of freedom, of truthfulness and of being true to the complexity of reality. Nothing is linear, it has always been important for me to make art with flexibility and movement.

SC Well, that seems to be what ‘Biting the Hand that Feeds’ is purely about.

Camille Henrot on why she selected Amazon Frontlines

‘’The preservation of the Amazon rainforest is a priority,

among the many emergencies related to the climate crisis.

Indigenous people of the region are defending the right to their own land, culture and survival in the Amazon.

I have followed several of the leaders over the years, and I found them inspiring.

It's an organization that gives hope.”

— Camille Henrot, 2024

Oil spills, extraction and biodiversity in the rainforest with Amazon Frontlines' Elena Manovella

We asked Amazon Frontlines' Development Coordinator how the NGO is working with local partners to save the rainforest.

ARTISTS SUPPORT Amazon Frontlines does a huge amount of varied and wide-spread work across the Rainforest, including protecting Indigenous ancestral land and knowledge, stopping oil extraction, funding grassroots Indigenous organizations, policy-making, educating youth in the region…the list goes on. What is Amazon Frontlines’ core mission?

ELENA MANOVELLA Our overall objective in the next five years is to scale and strengthen Indigenous guardianship of the Upper Amazon region, encompassing over 15 million hectares of primary rainforest through the implementation of four core strategic aims developed over a decade of shared work with Indigenous leaders to reclaim their lands, defend their rainforests, empower their communities and amplify their movements.

AS You're the Development Coordinator at Amazon Frontlines, what does that role entail?

EM I’m dedicated to fundraising and organizational growth at Amazon Frontlines. I write and manage grants to ensure that all funds are used effectively, meeting both donor requirements and the programmatic needs of the Indigenous communities we serve in the Upper Amazon.

We also operate a grant-making facility that provides essential funding to Indigenous-led organizations across the region. Our goal is to empower our Indigenous partners to become more autonomous and secure direct funding to support their mission. So I’m working to build their fundraising capacity through training and hands-on technical assistance.

AS You work with so many Indigenous partners on the ground. How is ancestral knowledge of the Amazon rainforest being recorded and passed down to younger generations?

EM Indigenous ancestral knowledge—the wisdom that has protected the Amazon rainforest for millennia—is at risk of being lost. As cultural assimilation threatens Indigenous communities, there’s a real urgency to preserve and revitalize this knowledge. That's why we support initiatives where Indigenous peoples patrol their territories, deterring threats and monitoring biodiversity. These efforts ensure that critical territorial knowledge is passed down. Elders lead the way, sharing their profound understanding of local flora and fauna, which they’ve gained through centuries of experience and the younger members document and learn, ensuring this knowledge is carried forward for future generations.

We also run a program that promotes intercultural education, combining scientific and Indigenous knowledge. We’re highlighting the importance of Indigenous teaching methods to preserve cultural heritage. It’s crucial for future generations to recognize the value of their territories and foster a deep connection to the land, cultivating a new generation of forest defenders to protect the rainforest and advocate for their communities.

AS Last year the Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations reported that rainforest territories protected by Indigenous peoples experienced 50% lower deforestation compared to any other land, and prevented huge amounts of CO2 emissions. How are you working with Indigenous people to secure their land?

EM One of the most effective ways to help Indigenous peoples protect their territories is through land titling, which gives them the legal authority to manage their forests. This starts with community-led mapping to define territory and to show Indigenous peoples’ deep ancestral and cultural connections to the land. These maps serve as proof of good stewardship and help secure official titles from the government.

Indigenous land titles are proving more effective than national parks at conservation, as protected areas often face greater threats from extractive industries. A good example is Yasuní National Park in Ecuador, one of the world’s most biodiverse regions. Despite its protected status, the park is vulnerable to oil extraction because it is government-controlled. Our mission goes beyond fighting big oil—we work to ensure that Indigenous communities, who are the rightful stewards of the land, have the power to protect it from these threats.

AS What are a few of the organization's greatest achievements to date?

EM Most of our achievements have been made with Ceibo Alliance, an NGO led by members of four Indigenous nations: Kofán, Siona, Secoya and Waorani. One of the most significant achievements we’ve made together is winning historical legal victories that have directly protected nearly 300,000 hectares of rainforest from gold mining and oil drilling. These victories have set a legal precedent that provides a tool for the protection of 9 million hectares of Ecuadorian rainforest. Together, we have also trained and equipped 200 Indigenous guards in 17 community land patrols with cutting-edge technologies to detect, document and deter illegal activities across 800,000 hectares of primary forest.

Since our beginnings, Amazon Frontlines has also focused on addressing critical livelihood needs. We have supported the community-led installation of 1,164 rainforest filtration systems across 80 communities affected by oil contamination in Ecuador, along with 155 solar-energy systems in 22 roadless communities, serving families, schools, and land patrol outposts.

And these are just a few examples of the many achievements we've made together over the years.

Wet Job refers to a series of paintings and sculptures of the same name in which Camille Henrot explores the limits of the post-partum body. It also refers to the conflicting pressures and expectations surrounding the body’s productivity. In the context of this exhibition, the title takes on additional meanings. ‘Wet Job’ is now also about such acts of care as washing or breastfeeding, and even about the fluidity of identity, about life and loss, and about the sometimes ‘messy’ or ‘mucky’ nature of dependency.

AS Could you elaborate on the significance of rainwater filtration systems?

EM They are vital for communities impacted by decades of oil extraction, especially in Ecuador, where water contamination is a serious problem. These systems collect rainwater and convert it into safe drinking water.

Chevron Texaco has been operating in Ecuador for over 50 years. The company has played a significant role in oil extraction which led to a major legal case addressing contamination caused by its activities. While the case had some initial success, affected communities have not received fair compensation and continue to suffer from the effects of pollution. Rainwater filtration systems are essential today because, although Chevron has left, new companies, including state-owned ones, have taken Chevron’s place. From 2005 to 2022, Ecuador experienced over 1,300 oil spills in the Amazon.

Oil is one of the most harmful pollutants and it hinders access clean water and fertile land. Supporting rainwater filtration systems and raising awareness about these issues are essential steps in helping these communities recover and thrive.

AS And it was in reaction to Chevron Texaco’s presence in the region that Amazon Frontlines was established.

EM Yes, Amazon Frontlines was founded when our current president, Mitch Anderson, met with four Indigenous leaders from the nations that now make up the Ceibo Alliance—those most affected by contamination from Chevron Texaco. The legal case against Chevron Texaco concluded in 2011 and it prompted these nations and leaders to recognize the need for direct action to improve conditions across their territories.

Mitch connected these leaders with international allies and advocates, which helped launch a project to install rainwater filtration systems in their communities. This initiative aimed to combat contamination and improve access to clean water, and equally important, it marked the first collaboration among these four nations, allowing them to share insights and experiences in the face of a common threat that had persisted for over 50 years.

More than just providing clean water, the project underscored the urgent need for unity in protecting Indigenous lands and the strength they hold as Indigenous peoples to act. This collaboration ultimately led to the formation of the Ceibo Alliance and Amazon Frontlines in 2014, with a mission to create a holistic model for Indigenous-led conservation in the Upper Amazon across Ecuador, Peru, and Colombia.

AS Last time we spoke we discussed how the organization has grown from a grassroots group to a global NGO. In 2016 you were awarded a $3 million multi-year grant from the DiCaprio Foundation. Was that a transformative moment?

EM Yes, that was a pivotal moment for our fundraising efforts. It was transformative because it offered flexible funding, which allowed us to cover crucial operational and administrative costs. This grant helped us establish internal structures and scale our programs, enabling us to reach more communities over time.

Over the past years we’ve significantly scaled our impact. The organization is at another critical moment as we were recently awarded the Hilton Humanitarian Prize, which is often referred to as the Nobel Prize for NGOs. This is the first time this award has been given to an organization focused on Indigenous peoples and climate issues–a testament to the success of our model.

AS That's fantastic. Congratulations. So what is next?

EM Our goal is to expand our grant-making capacity to better support our current partners and reach new organizations that are in need of direct funding. We would like to be recognized throughout the region for channeling resources to the Indigenous movement across the Upper Amazon. We want our grants to fund complementary initiatives from various organizations all working toward the common goal of rainforest protection.

At the same time, we want to increase our emergency funding, which is crucial for ensuring the safety of Indigenous leaders. The number of leaders killed in the region is alarming.

We have an overall goal to protect over 15 million acres of primary rainforest in the next 10 years, but I think one of the most important things we need to do is empower Indigenous communities, both politically and culturally, to recognize the significance of their territories and secure their protection and survival for future generations.